Beyond Consumption vs Creation

One of my favourite pieces I’ve ever written. Holds up immensely well, I think.

When the iPad first launched, many people reached for a quick analysis that it was a device “only for content consumption”. Despite time and experience having proven those people quite obviously wrong, the debate seems to persist as to what the iPad is, precisely, for.

My own opinion is that the iPad is for about 80% of all tasks you can conceivably do on a computer. I have never thought of the iPad as a distinct entity requiring a total first-principles relearning of what it means to use a computation device.

As I’ve written before, the question what you want to do with your computer has never had more impact on exactly the device you should buy. Therefore, it’s still relevant and worthwhile to ask the question of the iPad: what are you capable of, and what are you best at? Further, as the iOS ecosystem has developed, another question: if I add these accessories to you, what can you do now?

Still, I feel that the consumption/creation split is far too simplistic a curve to grade these devices on. It recognises almost nothing about the user’s task beyond whether it’s an input task or an output task. There’s far more subtlety that we can reach for.

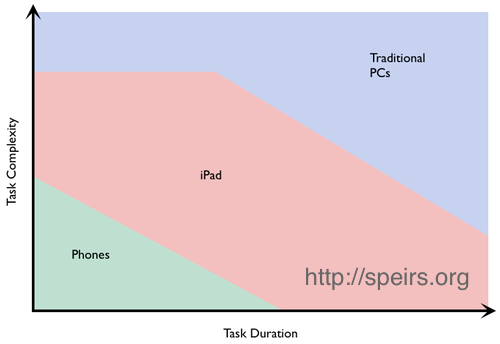

I’d like to propose a more useful pair of axes on which we can place these devices - smartphones, tablets and traditional PCs - than simply consumption/creation. I’ve been thinking about this for some time and I think it has some usefulness.

Task Complexity vs Task Duration

I’d like to propose that we can look at the ‘sweet spot’ for each type of device along two axes: task complexity and task duration. Task duration is the more obvious of the two: how long of a continuous period will you be using your device for the task.

Task complexity requires a little more unpacking. When I talk of “complexity”, I’m looking at a combination of factors that make a task complex:

- The number of steps to completion

- The extent to which you’re combining data from multiple sources

- The amount of data that is being manipulated

- The linearity or otherwise of those steps - the less linear, the more complex the task

There may be other types of complex task that I haven’t thought about. The exact specifics don’t matter too much but these give you the general idea.

Given that, here’s a chart of how I think about the ‘sweet spot’ for each type of device.

So what does this chart really say?

I place smartphones near the origin. They’re good for simple tasks done for a middling duration or tasks of moderate complexity for a short period. For example gaming, which is a fairly non-complex task, can be quite acceptable on a smartphone for a reasonable amount of time. On the other hand, editing a spreadsheet on an iPhone can be done but it’s not something you’d want to do for a whole day of working. Many of the most effective phone apps that take you through a series of steps do so in a very linear and directed fashion.

The iPad section of the chart has a couple of notable features: the dog-leg area at the top-left and the area at the bottom-right of the chart. Let’s dig into those.

Firstly, consider tasks of maximum complexity done over any duration: the iPad doesn’t reach into that area of the graph at all. That’s simply because there are some tasks of sufficient complexity that the iPad cannot currently be applied to them. The reasons are varied but fall into one of three areas:

- The hardware is not powerful enough yet. Examples here would include managing an entire high-resolution photographic library in a hypothetical “Aperture for iOS”. The iPad simply doesn’t have enough storage to make this possible, although the new 128GB iPad may well take a bite into some of these data-intensive tasks.

- The software has not been written yet. An example might be doing some CAD/CAM design. Perhaps iOS doesn’t offer all the APIs required for some apps yet. We can hope that iOS 7 will start to eat into some of these tasks.

- App Store policy doesn’t allow it. The classic example here is all the programming tools that we might wish to have on iOS which can’t be brought wholly to iOS until policy changes.

Similarly, there are tasks of low-to-medium complexity that can be adequately performed on an iPad for long periods of time. Examples might include annotating PDF documents with some of the excellent PDF apps on iOS, or managing photos in iPhoto, composing music in GarageBand, reading iBooks and so on.

In the middle of the chart lies a broad area of tasks which are moderately complex, done for moderate amounts of time. This is where iPad excels and why it is such an excellent computer for schools. I’ve never argued that any current or past iOS device can “do everything” - patently, it cannot - but I do argue that it can handle 95-100% of everything a computer is typically called on to do in a school setting. The majority of our classes now use iOS exclusively, despite easy access to Mac laptops being available.

Finally, there remain several tasks for which computers are used which tablets remain unsuitable for the reasons listed above. Simply think of the apps that are missing from iPads: Final Cut Pro X, Aperture, Logic Pro, iBooks Author, Adobe Photoshop. These tasks - for now - remain the preserve of the traditional “desktop-class” PC (in which category I include laptops).

What would it take to push iPad into some of those areas? Well, the simple addition of a hardware keyboard can extend the duration that many people can use their iPad for.

Taking another step into the PC’s territory may also call for something I’ve never really discussed before: a larger iPad. It’s possible that a 13” or 15” iPad with 128GB of storage might open up entirely new categories of application to be built for iOS.

You can see that, with the iPad mini pushing down towards smartphone territory and the 128GB iPad enabling a certain number of data-intensive use cases, the reach of the iPad is growing. I hope that, in time to come, future versions of iOS will enable software supporting tasks of greater complexity to be built.

I think that task complexity vs duration is a much more useful framework in which to place smartphones, iPad and traditional PCs. There may be other areas of comparison - for example the physical context of use - but I strongly believe that we have to move beyond simplistic arguments about consumption and creation.